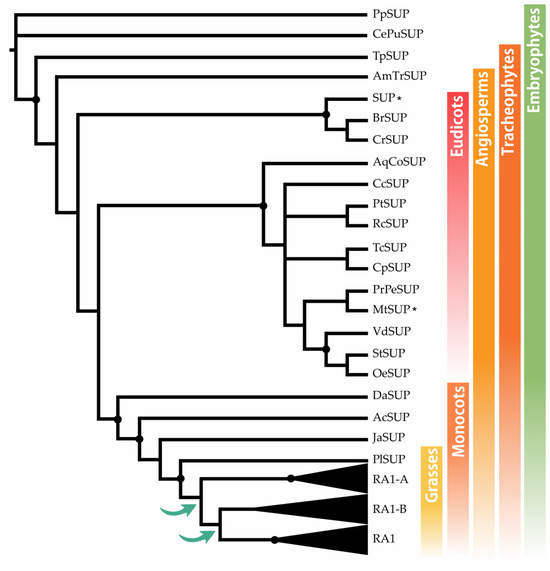

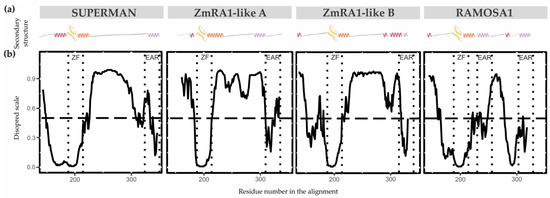

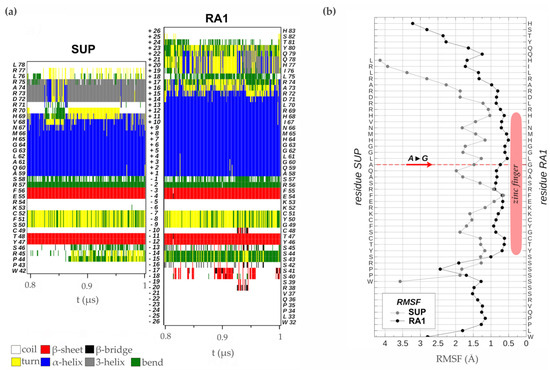

RAMOSA1 (RA1) is a Cys2-His2-type (C2H2) zinc finger transcription factor that controls plant meristem fate and identity and has played an important role in maize domestication. Despite its importance, the origin of RA1 is unknown, and the evolution in plants is only partially understood. In this paper, we present a well-resolved phylogeny based on 73 amino acid sequences from 48 embryophyte species. The recovered tree topology indicates that, during grass evolution, RA1 arose from two consecutive SUPERMAN duplications, resulting in three distinct grass sequence lineages: RA1-like A, RA1-like B, and RA1; however, most of these copies have unknown functions. Our findings indicate that RA1 and RA1-like play roles in the nucleus despite lacking a traditional nuclear localization signal. Here, we report that copies diversified their coding region and, with it, their protein structure, suggesting different patterns of DNA binding and protein–protein interaction. In addition, each of the retained copies diversified regulatory elements along their promoter regions, indicating differences in their upstream regulation. Taken together, the evidence indicates that the RA1 and RA1-like gene families in grasses underwent subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization enabled by gene duplication.

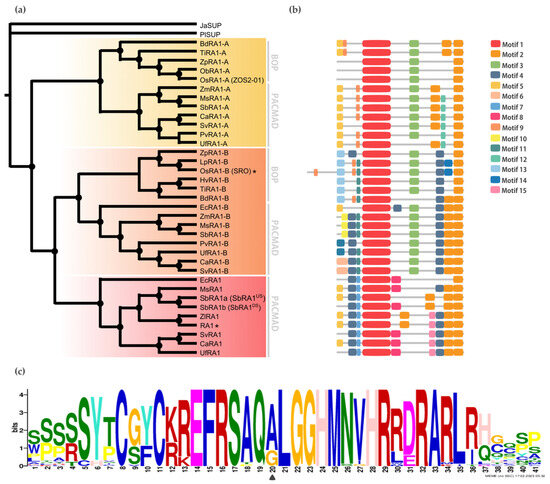

Conserved Motifs Analysis among RA1 and RA1-Like Coding Sequences

To discover specific features that characterize the coding region of each lineage, we performed a motif analysis (b). We searched for 15 different motifs using MEME to better understand sequence plasticity (

Figures S7 and S8). Some of them are lineage-specific (for instance, Motif 7 (WPPPQVRS), Motif 8 (PPPNPNPSCTVLDL), Motif 11 (FPWPPQ), Motif 12 (VVCSCSST), and Motif 13 (MESRSAARAGDQQH)), and others are shared by lineages, such as Motif 3 (ARAPJPNLNYSPPHPA), which is present in RA1-like A and RA1-like B sequences, whereas Motif 4 (APPVVYSFFSLAASA) is shared by RA1 and RA1-like B sequences (b and

Figure S7). All the sequences have in common the presence of one C2H2 zinc finger domain (Motif 1 (SSSSSYTCGYCKREFRSAQALGGHMNVHRRDRARLRHGQSP)) (b and

Figure S9). In particular, sequences from RA1 lineage have the variant QGLGGH in the zinc finger domain, as it was previously reported [

2] (c). In addition, Motif 2 (GDGAEEGLDLELRLG) appeared two to three times towards the C-terminal of all the sequences. Our analysis identified two Motif 2 along the C-terminal of the RA1-like sequences, whereas three Motif 2 were detected on most of the RA1 sequences of the PACMAD clade (b and

Figure S9). In addition, we found that the number of Leu (L) and the distances between the Motifs 2 vary among clades (b and

Figure S9). According to the literature, Motif 2 is a putative EAR-like repressor motif [

2,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements Analysis among RA1 and RA1-Like Promoter Sequences

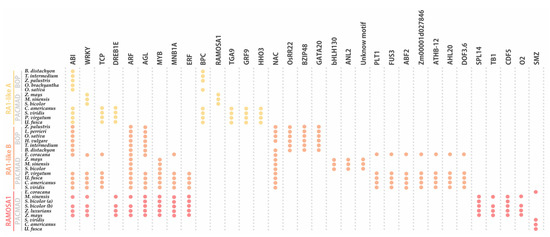

When the promoter of

RA1 and

RA1-like genes of 16 grass species were examined, many regulatory motifs were identified and grouped into 33 types of elements, according to the corresponding transcription factor (TF) family (,

Table S5). Conserved sequences containing binding motifs for well-known transcriptional regulators were recognized. We identified TF motifs involved in different biological processes related to (1) seed germination, such as embryo development, somatic embryogenesis, and positive regulation of cell population proliferation; (2) plant development, such as regulation of secondary shoot formation, leaf development, flower development, and root development; (3) response to abiotic stress, such as response to salt stress, response to light stimulus, and response to water; and (4) response to biotic stress, such as defense response to bacterium (

Table S6). In addition, we identified TF binding sites related to positive or negative regulation of hormone signaling pathways, hormone biosynthetic processes, as well as auxin, gibberellin, abscisic acid, and ethylene responses (

Table S6).

Figure 6. Noncoding

cis-elements identified in predicted promoter regions of

RA1 and

RA1-like genes from grass species. Colored circles represent presence of conserved motifs in the promoter. Motif consensus sequences are showed in

Table S5.

The conserved regulatory motifs harbored nine putative TF binding sites for RA1-like A lineage, 22 putative TF binding sites for RA1-like B lineage, and 13 putative TF binding sites for RA1 lineage. We found two conserved motifs shared by RA1-like and RA1 promoter sequences: (1) ABI-motifs are present among at least 24 of 35 promoter sequences analyzed; (2) WRKY-motifs were identified in 12 of 35 promoter sequences.

RA1-like A shares (1) TCP-motifs with the promoter sequences of RA1-like B of the PACMAD clade, except for the ones of Andropogoneae, and (2) DREB1E-motifs with Andropogoneae promoter sequences of RA1.

RA1-like B has five motifs in common with RA1: (1) ARF-motifs are present in all RA1-like B and RA1 promoter sequences of the Andropogoneae tribe; (2) AGL-motifs are well conserved in RA1-like B promoter sequences, except in the Andropogoneae tribe, while AGL-motifs are restricted to the Andropogoneae tribe in RA1 lineage; (3) MYB-motifs were identified in RA1-like B sequences of the PACMAD and RA1 promoter sequences from the Andropogoneae tribe; (4–5) MNB1A-motif and ERF-motifs were identified among RA1-like B promoter sequences of the PACMAD clade, except for the ones of Andropogoneae, and RA1 promoter sequences from the Andropogoneae tribe.

We found that each species lineage copy is characterized by unique cis-elements. The RA1-like A lineage has conserved BPC-motifs outside the Andropogoneae tribe and a RA1 binding motif in the Andropogoneae tribe. TGA9-motif, GRP9-motif, and HHO3-motif were identified only in promoter sequences from PACMAD clade species outside the Andropogoneae tribe. The RA1-like B lineage is characterized by the presence of NAC-motifs on all promoter sequences analyzed, except for the one of T. intermedium. OsRR22-motif, BZIP48-motif, and GATA20-motif are restricted to the BOP clade. Between species from the PACMAD clade, bHLH130-motif, ANL2-motif, and an unknown motif were identified in the Andropogoneae tribe, while PLT1-motif, FUS3-motif, ABF2-motif, Zm00001d027846-motif, ATHB-12-motif, AHL20-motif, and DOF3.6-motif were identified outside the Andropogoneae tribe. Finally, the promoter sequences of the RA1 lineage are characterized by the presence of (1) SPL14-motif, TB1-motif, CDF5-motif, and O2-motif sequences in the Andropogoneae tribe and (2) SMZ-motif outside the Andropogoneae tribe.